How big is a neighbourhood?

A lot smaller than the NHS thinks.

When you hear the question, ‘Tell me about your neighbourhood,’ what comes to mind? For most people, it’s their estate, village, small town, or a patch of an urban area. They think about familiar places: the local primary school, GP practice, place of worship, pub, park, and so on.

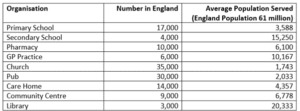

These places matter because they shape daily life—and they typically serve fewer than 10,000 people. Here’s some examples:

The problem: The NHS definition of ‘Neighbourhood’

For no discernible reason, other than perhaps convenience, the health system defines neighbourhoods as much larger areas. Integrated Neighbourhood Teams (INTs) are being set up across the country, typically covering 50,000 people or more.

While INTs aim to foster collaboration between local people, voluntary groups, and statutory organisations, the scale is wrong. At 50,000 people, most local organisations disengage because it’s not relevant to them.

Imagine an INT meeting for 50,000 people. That could involve:

- 14 primary schools

- 3 secondary schools

- 8 pharmacies

- 5 GP practices

- Over 20 faith organisations

- 25 pubs

- 11 care homes

- 2 libraries

That’s 85+ organisations, not counting scores of other community groups. No wonder they don’t show up, why would they? At best they get their views represented by someone else but in the main they just don’t engage. Relationships aren’t built, and local voices aren’t heard.

It gets worse

The government’s new National Neighbourhood Health Implementation Programme (NNHIP) has chosen 43 ‘Wave One’ “neighbourhoods”—places like Coventry, Herefordshire, and Barking & Dagenham. These aren’t neighbourhoods; they’re local authority areas with hundreds of thousands of people.

This approach doesn’t strengthen neighbourhoods or empower local organisations. It misses the chance to build social connections and improve health where it matters most.

The missed opportunity

Hyper-local organisations—schools, faith groups, pubs, community centres—could help the health system by:

- Identifying people at risk of health conditions (case finding)

- Supporting faster hospital discharge

- Helping to reduce missed outpatient appointments

- Increasing screening, immunisation and vaccination rates

- Cutting unnecessary A&E visits

A neighbourhood of 10,000 people will consume £25–£30 million in health spending annually. There’s no shortage of money—just a failure to invest in prevention at the right scale.

The question the health system should be asking community organisations in neighbourhoods of 10,000 people or less:

“It costs us £30m a year to support the health and wellbeing of people living in this neighbourhood. How can we help you to build a stronger, healthier place that puts less pressure on us?”