Volunteering can be the catalyst for NHS Hospitals to build healthier more resilient communities.

/0 Comments/by Giles PiercyAndrew Lansley’s reforms of the health system (in 2012) created the commissioner/provider spilt, effectively putting providers such as hospital trusts into a position where their primary focus was to treat patients when “commissioned” to do so. In effect, hospital trusts, one of the most significant components of our health and care system, were deliberately distanced from thinking about how to prevent demand on themselves. In fact, they were paid to treat patients and the more patients they treated the more they got paid, albeit they are public rather than private enterprises. At one level, given such structures and incentives in place it is unsurprising that they regularly became overwhelmed with demand. Until recently, though, that remained largely the concern of commissioners not the hospitals themselves, or at least not until demand reached crisis point.

Recent changes that have come into place in the health and care system since July 2022 have thankfully largely dismantled this commissioner/provider split. Finally, hospitals, as partners in Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) and Place Based Partnerships, are now forced to think about their role in building stronger healthier places, places that ultimately will put less pressure on the health and care system. As critical local institutions, hospitals are being asked to play an “Anchor Role” in their local communities. The Health Foundation describes “anchor institutions” as large organisations whose long-term sustainability is tied to the wellbeing of the populations they serve. Extraordinary really that this needs to be set out now (as if this wouldn’t have been at the heart of what all hospitals were trying to do). It does reveal how far many hospitals have strayed from where they were before the NHS was established.

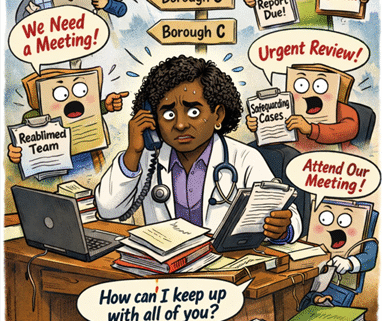

So, at a time of unrelenting pressure on the health system, how do Hospital Trusts find the time and capacity to play that role in their local communities? Our experience through working with different Trusts has been that they are generally too busy to be able to devote resources and time to preventative, health creating, community building activity. However perverse that may sound. Through having worked alongside Helpforce with several Acute (Hospital) Trusts we believe that volunteering may be a route for enabling Trusts to become meaningful contributors in building stronger, healthier, communities.

Trusts are now being asked to think about what they can do to support patients at all stages in their journey through the health system. How do they ensure patients are prepared for their hospital visit or appointment, how do they ensure their experience in hospital is as good as possible, how do they ensure people recover as quickly as possible once back home and how do they contribute to building healthier communities? Getting these things right will, amongst others, have significant impact on:

- Reducing health inequalities

- Reducing time in hospital

- Reducing missed appointments

- Reducing re-admission rates

- Speeding up diagnosis

- Encouraging greater take up of vaccination, immunisation and screening services – particularly from marginalised communities.

So where do volunteers come in?

Almost uniquely amongst statutory health and care providers, hospitals have a long and successful tradition of working with volunteers. Almost every hospital in the country will be supported by volunteers in different ways. They carry out all kinds of tasks from running cafes, to collecting prescriptions for patients, to being meal time companions, and so on. Many hospitals have 100s of volunteers on their books providing invaluable support. We believe this experience of working with volunteers and the presence of this volunteer work force in all Trusts can be the catalyst for Trusts effectively reaching out into their local communities to drive improvement in health outcomes and deliver on their obligations to be anchor organisations.

So much of the demand that faces the health system is only in part driven by ill health. So often the root cause (or wider determinant) of the issue is something that a volunteer could have helped to fix.

- Women from ethnic minority groups are nervous about attending cervical cancer screening leading to delayed diagnosis.

- People miss appointments because they can’t get transport or can’t understand the letters that are sent to them.

- People’s loneliness drives them to seek medical support when in fact they need support to be better connected to their local communities.

- People don’t attend community events because they are anxious or need accompanying.

- People can’t be discharged from hospital because they’ve no one to help them once at home.

- People visit A&E because they are unaware of other services, they can make use of.

- And so on

So many people are willing to help their neighbours but are unsure how. Because of our work alongside partners in health and care systems, we are certain hospitals have a significant role to play in building stronger more resilient communities where volunteering is much more widely practiced. We believe the starting point for this should be looking at the touch points between patients being at home and being in the hospital, and looking to identify and support volunteering that can substantially ease the pressure on health systems by identifying and supporting roles for volunteers where they are supporting people before, during and after they visit hospital.

If you would like to find out more about our work in this area, please contact gilespiercy@.

Work at our level don’t ask us to work at yours

/0 Comments/by Giles PiercyGiles Piercy as part of his involvement in Power to Change’s Community of Practice recently wrote this blog for Power to Change’s website you can read here

Contact Information

Phone: 07710 381436

E-Mail: enquiries@

Web: www.localitymatters.co.uk